Ernst Haeckel and his assistant Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay, photographed in the Canary Islands in 1866. From Wikimedia Commons.

In the nineteenth century, the study of radiolarians was the domain of German scientists. These early German workers laid the foundation for all future work with this group of organisms, both living and fossil.

Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795–1876) made a series of special monographs from 1838 to 1875 and named the group Polycystina. He described a half-dozen species of both Spumellaria and Nassellaria. Ehrenberg’s microscopic researches also included diatoms and fossil cyst of dinoflagellates. His book “Mikrogeologie” (1854) has many illustrations of a great number of microfossils.

Many of Ehrenberg’s early radiolarian species descriptions come from Neogene biosiliceous sediments of Italy. Despite the fact he worked before the concept of type specimens for species had become established, Ehrenberg not only documented most of his species with published figures, but preserved the original material and microscope preparations for future generations of scientists to study (Lazarus 2014).

Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg and Johannes Müller. Source: Museum für Naturkunde,

Berlin and Humboldt Universität, Berlin.

Johannes Müller (1801–1858), one of the most famous German biologists of his generation, published three substantial papers on radiolarians. He described a total of 69 species, including both polycystines and acantharians. As a professor on Berlin’s Medical Faculty, he influenced a great number of students. Among them were Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) and Rudolf Virchow (1821-1902).

Like Ehrenberg, Müller never believed that species had evolved over time, and he died before the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species.

After Müller’s death, E. Haeckel focused on the group last studied by his friend and professor: the radiolarians. With a copy of Müller’s paper and a wealth of material available off Messina, Haeckel began the first of his major studies of nature.

In 1862, Haeckel made the first complete classificatory system for the Radiolaria and produced finely detailed drawings of them in his book: “Die Radiolarien”. He dedicated this monograph to Müller. In this work, he included polycystines, phaeodarians and acantharians.

In 1864, Haeckel sent to Darwin, two folio volumes on radiolarians. The gothic beauty of these drawings impressed Darwin. He wrote to Haeckel that “were the most magnificent works which I have ever seen, and I am proud to possess a copy from the author”.

Haeckel became the most famous champion of Darwinism in Germany and he was so popular that, previous to the First World War, more people around the world learned about the evolutionary theory through his work “Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte” (The History of Creation: Or the Development of the Earth and its Inhabitants by the Action of Natural Causes) than from any other source. His study of radiolarians established Haeckel as a young scientist of importance. Later, Haeckel focused his research in the more general aspects of evolution and development.

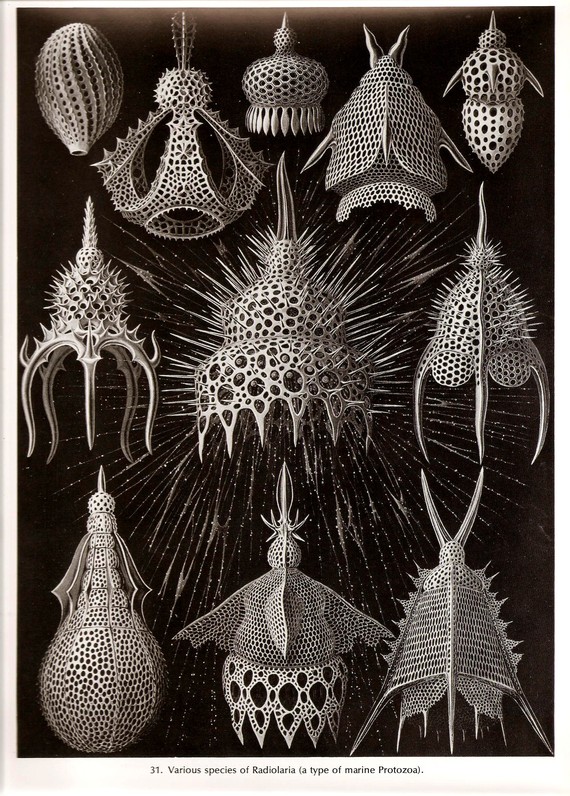

Ernst Haeckel’s ”Kunstformen der Natur” (1904), showing Radiolarians of the order Stephoidea. From Wikimedia Commons.

Along with many other scientists, Haeckel was asked by the managers of the Challenger Expedition soon after the ship’s return to examine and report on the expedition’s collections specifically for radiolarians, sponges and jellyfish. Haeckel’s Report on Radiolaria took him almost a decade.

His final report was published in 1887 and summarized and subsumed all prior work on radiolarians up to that point, including, for example, many of Ehrenberg’s species and genera. But while Ehrenberg eschewed higher taxa, except for a minimally adequate number of obvious, high-level groupings, Haeckel did the opposite thing and introduced a much enlarged and substantially more complex higher-level taxonomy for the radiolaria generating numerous duplicate lower-level categories, including species, which led to an unusually large percentage of Haeckel’s named species being ignored as redundant or meaningless (Lazarus, 2014).

In 1904, Haeckel published his master work “Kunstformen der Natur” (Art Forms of Nature) and helped to popularize radiolarians among scientists and the general audience.

Karl Alfred Ritter von Zittel (1839-1904), was a prominent German paleontologist. His early research was in minerals and petrography. In 1876, he published “Ueber einige fossile Radiolarien aus der norddeutschen Kreiden. Zeitschrift der deutschen geologischen Gesellschaft” where he described Mesozoic radiolarians in northern Germany. Many of the species names proposed by Zittel are still valid today.

David Rüst (1831–1916) published 10 papers on radiolarians. Although he was not the first to describe Mesozoic radiolarians, he was certainly the most prolific describing over 900 new species of fossil radiolarians from Mesozoic and even Palaeozoic rocks from Europe and North America.

References:

David Lazarus, The legacy of early radiolarian taxonomists, with a focus on the species published by early German workers, Journal of Micropalaeontology 2014, v.33; p3-19.

Robert J. Richards, The Tragic Sense of Life: Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought, (2008), University of Chicago Press.

Pingback: Haeckel and the legacy of early radiolarian tax...

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. 11 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol: #36 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #32 | Whewell's Ghost