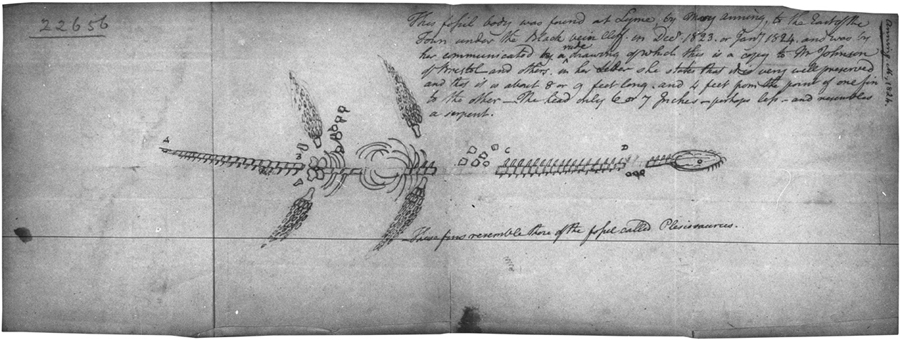

Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus found by Mary Anning. From: W D Conybeare, 1824

Mary Anning was born on Lyme Regis on May 21, 1799. Her father was a carpenter and an amateur fossil collector who died when Mary was eleven. He trained Mary and her brother Joseph in how to look and clean fossils. After the death of her father, Mary and Joseph used those skills to search fossils on the local cliffs, that sold as “curiosities”. The source of the fossils was the coastal cliffs around Lyme Regis, one of the richest fossil locations in England and part of a geological formation known as the Blue Lias.

On December 10, 1823, Mary Anning discovered the first complete Plesiosaur skeleton at the same cliff where she found the Ichthyosaur. The new creature had a tiny head and a remarkable long neck. She sent a number of letters addressed to Sir Henry Bunbury, a member of the Geological Society, and to William Buckland, provinding a sketch and a detailed description of the three metre by two metre wide specimen.

In one of the letters to Bunbury she wrote: “Sir. I have endeavoured in a rough sketch to give you some idea of what it is like. Sir you understand me right in thinking that I said it was the supposed plesiosaurus [sic], but its remarkable long neck and small head, shows that it does not in the least verifie [sic] their conjecturs [sic]; in its Analogy to the Ichthyasaurus, it is large and heavy but one thing I may venture to assure you it is the first and only one discovered in Europe, Colonel Birch offered one hundred guineas for it unseen, but your letter came one day past before [but] I consider your claim to be an answer prior to this, Should you like it the price I ask for it is one hundred and ten pounds, one hundred guineas was my intended price, but if take the same sum as Col B offered he would think I had used him ill in not taking his money.”

Mary Anning´s letter to H. Bunbury from December 19, 1823, about the discovery of a plesiosaur. From the Wellcome Collection..

These letters reveals the scientific networks where Mary Anning was involved in as a fossil dealer. Buckland, for its part, informed about the discovery to Richard Grenville, first Duke of Buckingham, who later purchased the fossil for 150 guineas.

William Conybeare, also heard about the specimen and hurried to Lyme Regis to see it in situ. In 1821, Conybeare and Henry de la Beche, described a partial skeleton discovered in the collection of Colonel Thomas James Birch, and named it Plesiosaurus (from the Greek word plèsios, “closer to”, and the Latin word saurus, “lizard”) meaning that the strange creature was more like a reptile. The new specimen acquired by the Duke of Buckingham was transported to the Geological Society for its meeting of 20 February 1824.

A sketch of a Plesiosaur by Mary Anning, 1824. From original manuscripts held at the Natural History Museum, London. © The Natural History Museum, London

Conybeare’s original account began as follows: “I AM highly gratified in being– able to lay before the Society an account of an almost perfect skeleton of Plesiosaurus, a new fossil genus, which, from the consideration of several fragments found only in a disjointed state, I felt myself authorized to propound in the year 1821, and which I described in the Geological Transactions for that and the following year. It is through the kind liberality of its possessor, the Duke of Buckingham, that this specimen has been placed for a time at the disposal of my friend Professor Buckland for the purpose of scientific investigation.”

Mary Anning not only discovered the skeleton, but she prepared the fossil and even made the sketch that Conybeare used in his presentation to the Geological Society. But Conybeare never mentioned Mary Anning in his work.

The plesiosaur purchased from Mary Anning by Constant Prevost.

Noticed about the oddity of the specimen, George Cuvier wrote to William Conybeare suggesting that the find was a fake produced by combining fossil bones from different animals. The unexpected proportions of the neck, raised the suspicions of Cuvier. But William Buckland and Conybeare sent a letter to Cuvier including anatomical details, an engraving of the specimen and a sketch made by Mary Morland (Buckland’s wife) based on Mary Anning’s own drawings and they convinced Cuvier that this specimen was a genuine find. From that moment, Cuvier treated Mary Anning as a legitimate and respectable fossil collector and unlike Conybeare, Cuvier cited her name in his publications.

In May 1824, Cuvier sent geologist Constant Prévost to England for an official geological trip, supported by the administration of the Palaeontology Gallery of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. In June 1824 Prévost – accompanied by Charles Lyell- went to Lyme Regis and met Mary Anning. He bought a plesiosaur for £10 and sent it to Paris. Cuvier included the engraving of his plesiosaur in a third edition of his “Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe”.

References:

Conybeare, William (1824), “On the Discovery of an almost perfect Skeleton of the Plesiosaurus”, Transactions of the Geological Society of London, Geological Society of London, S2-1 (2): 381–389, doi:10.1144/transgslb.1.2.381, S2CID 129024288

Davis, Larry E. (2012) “Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness,”The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon: Vol. 84: Iss. 1, Article 8.