Duria Antiquior famous watercolor by the geologist Henry de la Beche based on fossils found by Mary Anning. From Wikimedia Commons.

By the 19th century, the study of the Earth became central to the economic and cultural life of Great Britain. Women were free to take part in collecting fossils and mineral specimens, and they were allowed to attend lectures but they were barred from membership in scientific societies. England was ruled by an elite, and of course, these scholarly activities only occurred within the upper echelon of British society. Notwithstanding, the most famous fossilist of the 19th century was a women of a low social station: Mary Anning.

Mary Anning was born on Lyme Regis on May 21, 1799. Her father was a carpenter and an amateur fossil collector who died when Mary was eleven. He trained Mary and her brother Joseph in how to look and clean fossils. After the death of her father, Mary and Joseph used those skills to search fossils that they sold as “curiosities”. The source of those fossils was the coastal cliffs around Lyme Regis, part of a geological formation known as the Blue Lias.

The shore of Lyme Bay where Mary Anning did most of her collecting.

Invertebrate fossils, like ammonoids or belemnites, were the most common findings. But when Mary was 12, her brother Joseph found a skull protruding from a cliff and few month later, Mary found the rest of the skeleton. They sold it for £23. Later, in 1819, the skeleton was purchased by Charles Koenig of the British Museum of London who suggested the name “Ichthyosaur” for the fossil.

In 1819 the Annings were in considerable financial difficulties. They were rescued by the generosity of Thomas James Birch (1768–1829), who arranged for the sale of his personal collection, largely purchased from the Annings, in Bullock’s Museum in London. The auction took place in May 1820, during which Georges Cuvier bought several pieces for the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle.

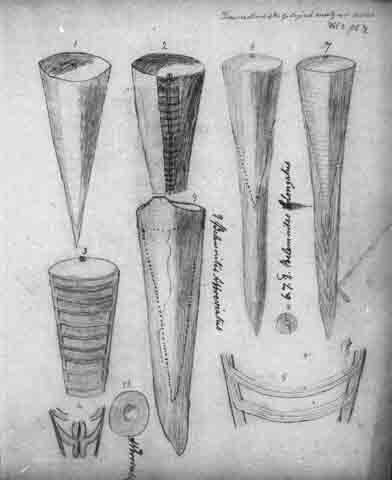

Mary Anning’s sketch of belemnites. From original manuscripts held at the Natural History Museum, London. © The Natural History Museum, London

On December 10, 1823, she discovered the first complete Plesiosaur skeleton at Lyme Regis in Dorset. The fossil was acquired by the Duke of Buckingham. Noticed about the discovery, George Cuvier wrote to William Conybeare suggesting that the find was a fake produced by combining fossil bones from different animals. William Buckland and Conybeare sent a letter to Cuvier including anatomical details, an engraving of the specimen and a sketch made by Mary Morland (Buckland’s wife) based on Mary Anning’s own drawings and they convinced Cuvier that this specimen was a genuine find. From that moment, Cuvier treated Mary Anning as a legitimate and respectable fossil collector and cited her name in his publications.

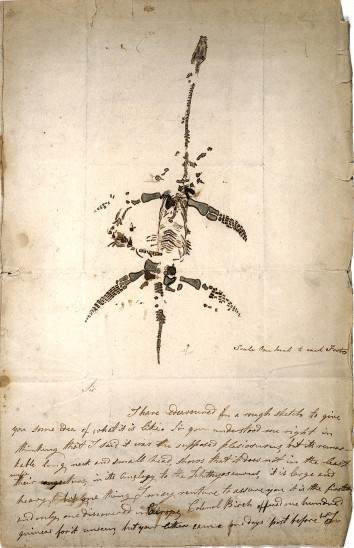

Autograph letter about the discovery of plesiosaurus, by Mary Anning. From original manuscripts held at the Natural History Museum, London. © The Natural History Museum, London

By the age of 27, Mary was the owner of a little shop: Anning’s Fossil Depot. Many scientist and fossil collectors from around the globe went to Mary´s shop. She was friend of Henry De la Beche, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who knew Mary since they were both children and lived in Lyme Regis. De la Beche was a great supporter of Mary’s work. She also corresponded with Charles Lyell, William Buckland and Mary Morland, Adam Sedgwick and Sir Roderick Murchison.

It’s fairly to say that Mary felt secure in the world of men, and a despite her religious beliefs, she was an early feminist. In an essay in her notebook, titled Woman!, Mary writes: “And what is a woman? Was she not made of the same flesh and blood as lordly Man? Yes, and was destined doubtless, to become his friend, his helpmate on his pilgrimage but surely not his slave…”

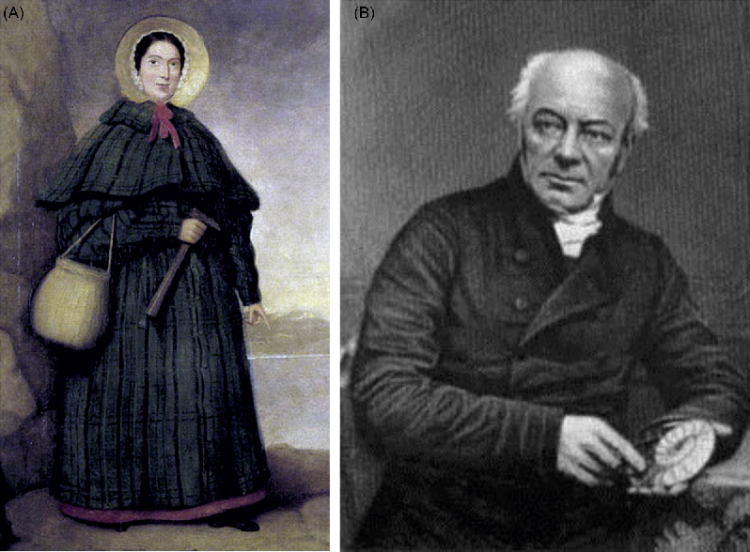

A) Mary Anning (1799- 1847) B) William Buckland (1784- 1856)

On December of 1828, Mary found the first pterosaur skeleton outside Germany. William Buckland made the announcement of Mary’s discovery in the Geological Society of London and named Pterodactylus macronyx in allusion to its large claws. The skull of Anning’s specimen had not been discovered, but Buckland thought that the fragment of jaw in the collection of the Philpot sisters of Lyme belonged to a pterosaur.

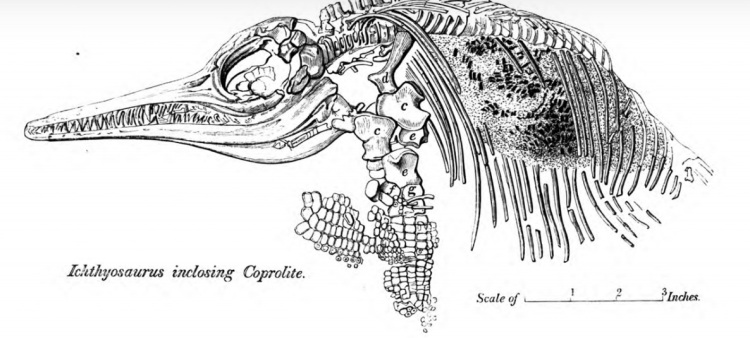

An illustration of Mary Anning’s ichthyosaur skeleton appeared in William Buckland’s book Geology and Mineralogy.

Mary Anning, ‘the greatest fossilist the world ever knew’, died of breast cancer on 9 March, 1847, at the age of 47. She was buried in the cemetery of St. Michaels. In the last decade of her life, Mary received three accolades. The first was an annuity of £25, in return for her many contributions to the science of geology. The second was in 1846, when the geologists of the Geological Society of London organized a further subscription for her. The third accolade was her election, in July 1846, as the first Honorary Member of the new Dorset County Museum in Dorchester.

After her death, Henry de la Beche, Director of the Geological Survey and President of the Geological Society of London, wrote a very affectionate obituary published in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society on February 14, 1848, the only case of a non Fellow who received that honour.

Mary Anning’s Window, St. Michael’s Church. From Wikimedia Commons.

In February 1850 Mary was honoured by the unveiling of a new window in the parish church at Lyme, funded through another subscription among the Fellows of the Geological Society of London, with the following inscription: “This window is sacred to the memory of Mary Anning of this parish, who died 9 March AD 1847 and is erected by the vicar and some members of the Geological Society of London in commemoration of her usefulness in furthering the science of geology, as also of her benevolence of heart and integrity of life.”

In 1865, Charles Dickens wrote an article about Mary Anning’s life in his literary magazine “All the Year Round”, where emphasised the difficulties she had overcome: “Her history shows what humble people may do, if they have just purpose and courage enough, toward promoting the cause of science. The inscription under her memorial window commemorates “her usefulness in furthering the science of geology” (it was not a science when she began to discover, and so helped to make it one), “and also her benevolence of heart and integrity of life.” The carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.”

References:

Buckland, Adelene: Novel Science : Fiction and the Invention of Nineteenth-Century Geology, University of Chicago Press, 2013.

BUREK, C. V. & HIGGS, B. (eds) The Role of Women in the History of Geology. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 281, 1–8. DOI: 10.1144/SP281.1.

Davis, Larry E. (2012) “Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness,”The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon: Vol. 84: Iss. 1, Article 8.

Hugh Torrens, Mary Anning (1799-1847) of Lyme; ‘The Greatest Fossilist the World Ever Knew’, The British Journal for the History of Science Vol. 28, No. 3 (Sep., 1995), pp. 257-284. Published by: Cambridge University Press.

De la Beche, H., 1848a. Obituary notices. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, v. 4: xxiv–xxv.

Dickens, C., 1865. Mary Anning, the fossil finder. All the Year Round, 13 (Feb 11): 60–63.

Pingback: Fossil Friday Roundup: May 25, 2018 | PLOS Paleo Community