It was the best of times. In the nineteenth century England, the Industrial Revolution started a time of important social and political change. London became the financial capital of the world. Several scientific societies were forming, such as the Geological Society of London and fascinating discoveries revealed part of the history of our planet. But it was also the worst of time. England was ruled by an elite, meanwhile most of the people were poor. Churches provided schools for poor children and infant mortality was high. During these difficult times, and despite her low social station, Mary Anning made some of the most significant geological finds of all time. She has been called “the Princess of Palaeontology” by the German explorer Ludwig Leichhardt and scientists like William Buckland or Henry de la Beche owe their achievements to Mary’s work.

Mary Anning was born on Lyme Regis on May 21, 1799. Her father was a carpenter and an amateur fossil collector who died when Mary was eleven. He trained Mary and her brother Joseph in how to look and clean fossils. After the death of her father, Mary and Joseph used those skills to search fossils on the local cliffs, that sold as “curiosities”. The source of the fossils was the coastal cliffs around Lyme Regis, one of the richest fossil locations in England and part of a geological formation known as the Blue Lias. The age of the formation corresponds to the Jurassic period.

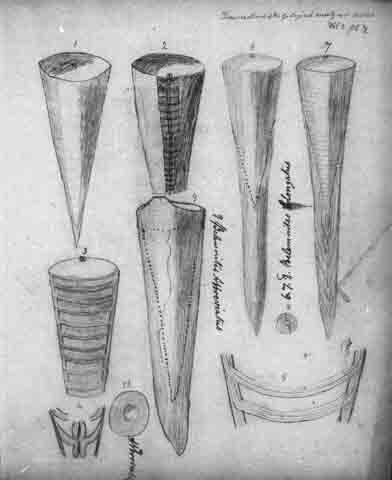

Mary Anning’s sketch of belemnites. From original manuscripts held at the Natural History Museum, London. © The Natural History Museum, London

Invertebrate fossils, like ammonoids or belemnites, were the most common findings. But when Mary was 12, her brother Joseph found a skull protruding from a cliff and few month later, Mary found the rest of the skeleton. They sold it for £23. Later, in 1819, the skeleton was purchased by Charles Koenig of the British Museum of London who suggested the name “Ichthyosaur” for the fossil.

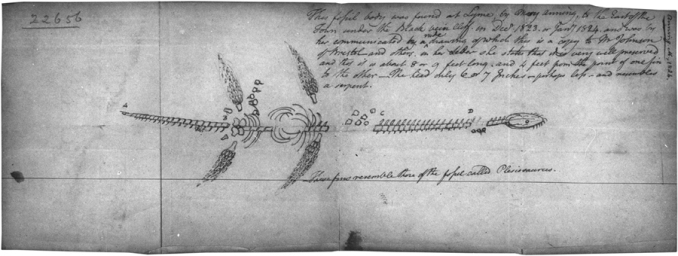

A sketch of a Plesiosaur by Mary Anning, 1824. From original manuscripts held at the Natural History Museum, London. © The Natural History Museum, London

In 1823, Mary made another amazing discovery. She found the first complete Plesiosaurus. Mary immediately wrote to William Buckland, the famous English geologist and paleontologist, describing the strange skeleton. By the age of 27, Mary was the owner of a little shop: Anning’s Fossil Depot. Many scientist and fossil collectors from around the globe went to Mary´s shop. But she was considered an outsider for the scientific community that often forgot to mention Mary’s name in the description of the specimens she found.

Duria Antiquior famous watercolor by the geologist Henry de la Beche based on fossils found by Mary Anning. From Wikimedia Commons.

Nevertheless she was friend of Henry De la Beche, the first director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, who knew Mary since they were both children and lived in Lyme Regis. De la Beche was a great supporter of Mary’s work. She also corresponded with Charles Lyell and Adam Sedgwick. On December, 1828, Mary found the first pterosaur skeleton outside Germany. William Buckland made the announcement in the Geological Society of London. Working with Buckland, Mary suggested that the “Bezoar stones” were fossilized feces. Buckland published that conclusion in 1829 and named them coprolites. In 1834, Mary assisted the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz during his visits to Lyme Regis. In her later years, Mary suffered some serious financial problems. De la Beche helped her during those hard times. Also William Buckland persuaded the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the British government to award her an annuity of £25, in return for her many contributions to the science of geology. Mary Anning died of breast cancer on 9 March, 1847, at the age of 47. She was buried in the cemetery of St. Michaels. In 1865, Charles Dickens wrote an article about her life in his literary magazine “All the Year Round”. He ended the article with these phrase: “The carpenter’s daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.”

References:

Davis, Larry E. (2012) “Mary Anning: Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness,”The Compass: Earth Science Journal of Sigma Gamma Epsilon: Vol. 84: Iss. 1, Article 8.

Goodhue, Thomas W (2005), “Mary Anning: the fossilist as exegete”, Endeavour 29 (1): 28–32, doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2004.11.004

Pingback: Giants’ Shoulders #60 Part II: The Present | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Pingback: Women in the Golden Age of Geology in Britain. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: Mary Anning’s contribution to French paleontology. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: Mignon Talbot and the forgotten women of Paleontology. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: Remembering Mary Anning. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #49 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Dorothea Bate: cave explorer and paleontologist. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: El plesiosaurio de la hija del carpintero - ¡Cuánta Ciencia!

Pingback: Mary Anning and the flying dragon. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: Mary Anning, the carpenter’s daughter. | ...

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #41 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: A brief history of Pterosaurs. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 3, Vol. #26 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: Mary Anning and the Hunt of Primeval Monsters. | Letters from Gondwana.

Pingback: Hopes rise for statue of pioneering fossil hunter Mary Anning | Tradition

Pingback: Hopes rise for statue of pioneering fossil hunter Mary Anning – HNM

Pingback: Hopes increase for statue of pioneering fossil hunter Mary Anning | Lifestyle - Out News

Pingback: Hopes rise for statue of pioneering fossil hunter Mary Anning – HNM

Pingback: Hopes rise for statue of pioneering fossil hunter Mary Anning – peter-travel.com

Pingback: Hopes rise for statue of pioneering fossil hunter Mary Anning – Swissnewss.com

Pingback: Hopes rise for statue of pioneering fossil hunter Mary Anning – Swissnewss.com