During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Paris was a busy place for science. In 1794 the Reign of Terror ended with the establishment of a new government that was more supportive of the sciences. The old Royal Botanical Garden and the affiliated Royal Museum were reorganized as the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle. The new institution fostered many brilliant scientists, including Cuvier, Lamarck, and St. Hilaire. Among those remarkable men was Alcide Dessalines d’Orbigny, considered the founder of micropaleontology and biostratigraphy. He worked in natural history, geology, paleontology, anthropology, linguistics, taxonomy and systematics.

Alcide d’Orbigny was born in Couëron (Charente-Maritime) on September 6th, 1802. In his early youth, he developed a life interest in the study of a group of microscopic animals that he named ‘Foraminifera’ and established the basis of a new science, micropaleontology. He started at an early age working with his father, a doctor, who introduced him to the study of microscopic shells they collected from La Rochelle, a major port on the coast of France. However, Bartolomeo Beccari, was the first to study these tiny shells that could only be observed under the microscope. Beccari analysed in detail the outer and inner structure of the shell, recognising the concamerations and the coiled structure, and attributed these organisms to microscopic ‘Corni di Ammone’, continuing with the enduring confusion between ammonites and foraminifera that started in 1565 when Conrad Gesner described the nummulites collected in the surroundings of Paris. Also Giovanni Bianchi (known by the pseudonym Jaco Planco) in his work ‘De conchis minus notis’ (1739) describes numerous microforaminifera that are found in abundance on the shoreline of Rimini and assigns them the name ‘Corni di Ammone’.

Cover of De conchis minus notis and foraminifera of Rimini’s seaside figured by Bianchi (1739, Table I) and attributed by the author to microscopic specimens of ‘Cornu Ammonis’.

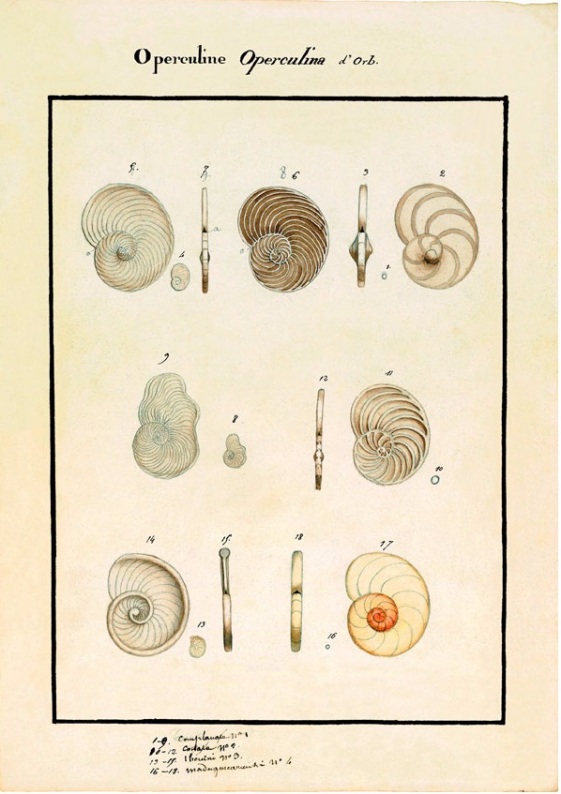

On November 7, 1825, d’Orbigny presented to the Académie des Sciences, the results of his observations in a work entitled ‘Tableau méthodique de la classe des Céphalopodes’. It’s clear that d’Orbigny also considered this group of microscopic shells as belonging to the Cephalopods. But he was the first to divide the Cephalopods into two zoological orders: the ‘Siphonifères‘ with intercameral siphon and ‘Foraminifères’ characterized by openings (or foramina) located in the septa separating two consecutive chambers. To illustrate his work, d’Orbigny prepared 73 plates of drawings and made models of 100 of his foraminiferal species that he sculpted in a very fine limestone.

There is a long gap between the publication of his pioneering work and his other works dedicated to foraminifera because of his long journey to South America documented in the nine volumes of his ‘Voyage dans l’Amérique Méridionale’ (1835–1847). In 1835, Félix Dujardin discovered that foraminiferans were not cephalopods, but single-celled organisms. This important discovery led d’Orbigny to exclude the foraminifera from the Cephalopods. In a work published in 1839, he traced the history of foraminiferal studies and considered them as a class for the first time, dividing the history of their study in four periods culminating with the revelation of their unicellular nature.

In the volume dedicated to the recent foraminifera collected in South America he pointed out the influence of currents, temperature and depth on their distribution patterns. In Mémoire sur les foraminifères de la craie blanche du bassin de Paris published in 1840, d’Orbigny demonstrated that foraminifera could be used for classifying geological strata.

D’Orbigny‘s legacy was extraordinary with thousands of species described, the occurrences of fossils documented chiefly in France, as well as his outstanding Le Voyage dans l’Amérique méridionale published between 1835-1847, and covering the biology, ethnology, anthropology, paleontology, and other aspects of Chile, Peru, Argentina, Uruguay, and especially Bolivia.

In 1853, Napoleon III created the Chair of Paleontology in the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in his honour. After his death on June 30, 1857, the collection of d’Orbigny, which includes more than 14,000 species and over 100,000 specimens not counting innumerable foraminifera stored in assorted glass bottles, was auctioned by his family. The collection was bought by the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, in 1858 and registered in the catalogue of the Paleontology Laboratory of this institution.

References:

d’Orbigny, A. 1826. Tableau méthodique de la classe des Céphalopodes. Annals des Sciences Naturelles, 1st Series, 7: 245-314.

Dujardin, F. 1835a. Observations sur les Rhizopodes et les Infusoires, Comptes Rendus, de l’Académie des Sciences, 1: 338-340.

Heron-Allen, E. (1917) Alcide d’Orbigny, his life and his work. Journal of the Royal Microscopic Society, ser. 2, 37, 1–105, 433–4.

Seguenza G. 1862. Notizie succinte intorno alla costituzione geologica dei terreni terziarii del distretto di Messina. Messina: Dalla Stamperia di Tommaso Capra. 84 pp.

Vénec-Peyré, M-T, 2004, Beyond frontiers and time: the scientific and cultural heritage of Alcide d’Orbigny (1802–1857), Marine Micropaleontology 50, 149 – 159.

thank you. one day i want to learn the history of the study of protists. I’m fasinated that it took so long to get moving from its begining with Leeuvenhoek!

Have you seen the AMNH’s “Shelf Life” on youtube yet? The newest episode is on their foraminifera collection.

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Vol. #46 | Whewell's Ghost

the museum in france opened a position to “replace D’Orbigny”. they gave the position to an ostracodologist and not a foraminiferologist. sad, very sad.

Very sad indeed